A rather unspectacular acrylic painting (V from the Brushstrokes series) from 2008 shows three color elements applied with determinedly broad brushstrokes on a white surface. A red color streak vertically running up the left edge of the painting dominates two smaller elements in green and ochre to the right. While the horizontal, ochre color stripe at the top adheres entirely to the surface, the green stripe below it, almost as if it were three-dimensional, protrudes into the heart of the picture; or, conversely, out of it like a fragment of an antique column lying on its side. Color and three-dimensionality, surface and space interact dialectically on the painting’s surface as a ground for painterly experimentation. Like his abstract-personal basic toolset, Hanvald has laid out the picture’s elements for the viewer to behold. Thus, these painted building blocks of his own visual universe seem like a fundamental reference to his compositionally much more elaborate and complex painterly constructions. However, in the end, it is always about the act of painting itself, too. Repeatedly, David Hanvald refers to contemporary influential artists such as Bruce Nauman, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, or Sigmar Polke, who are sometimes quoted quite directly by him. Nevertheless, and at least as obviously, the more recent historical tradition of his home country and artistic environment plays a part in his art. Hanvald also draws on the tradition of Constructivism, the artists of the Vkhutemas and the Bauhaus, whose influences were also reflected in the Czech avant-garde, though he rarely refers to them explicitly. As if floating freely in space in his paintings, the scaffold-like constructions, for example, show direct parallels not only to Sol LeWitt (like in some of his paintings from the Objects series). Parallels exist also and particularly to constructivist compositions of the artistic avant-garde in the early 20th century. Hanvald establishes a direct associative connection between El Lissitzky and Donald Judd by creating two compositions of his own quoting the artists and juxtaposing them in a dialog. In earlier works on paper, on the other hand, strokes, curves, and lines drawn with effortless ease take on a life of their own, stylistically preceding the geometric rigor of his later paintings and more reminiscent of Kandinsky’s compositions in the context of “point and line to plane.” In any case, with David Hanvald, there is a fair amount of art history involved. And he draws on it more like a toolset than he intends to continue it linearly. More important than the historical linearity is always the associative approach: bringing together, merging as well as dividing geometric forms, cubes, triangles, semicircles, angles; giving them a new life within the painting. David Hanvald draws on a wealth of material, including echoes of constructivist architectural drawings, such as in his work Synagogue or in Brick, as well as architectural elements in general. Moreover, he juxtaposes the imagined three-dimensional constructions in many of his paintings with real sculptural objects – three-dimensional complements, primarily serving as modules in the context of space-related exhibition presentations, rather than as solitary sculptures. Thus, paintings and sculptures merge to become a unique spatial hybrid. One example of this concept is object No. 20 from the Kunst History series shown on pp. 52/53. In it, canvas-covered stretcher frames are arranged on top of each other like drawers, with thin wooden panels between them. The surfaces of the paintings inside remain hidden to the eye; only their front sides and the wooden panels show traces of paint, indicating that there must be painted canvases inside. In this case, the connection to Donald Judd is particularly evident; the reference is obvious. But at the same time, Hanvald’s block also acts as an energy collector containing his art, as a kind of abstract color accumulator that is both a quotation and a new source of inspiration.

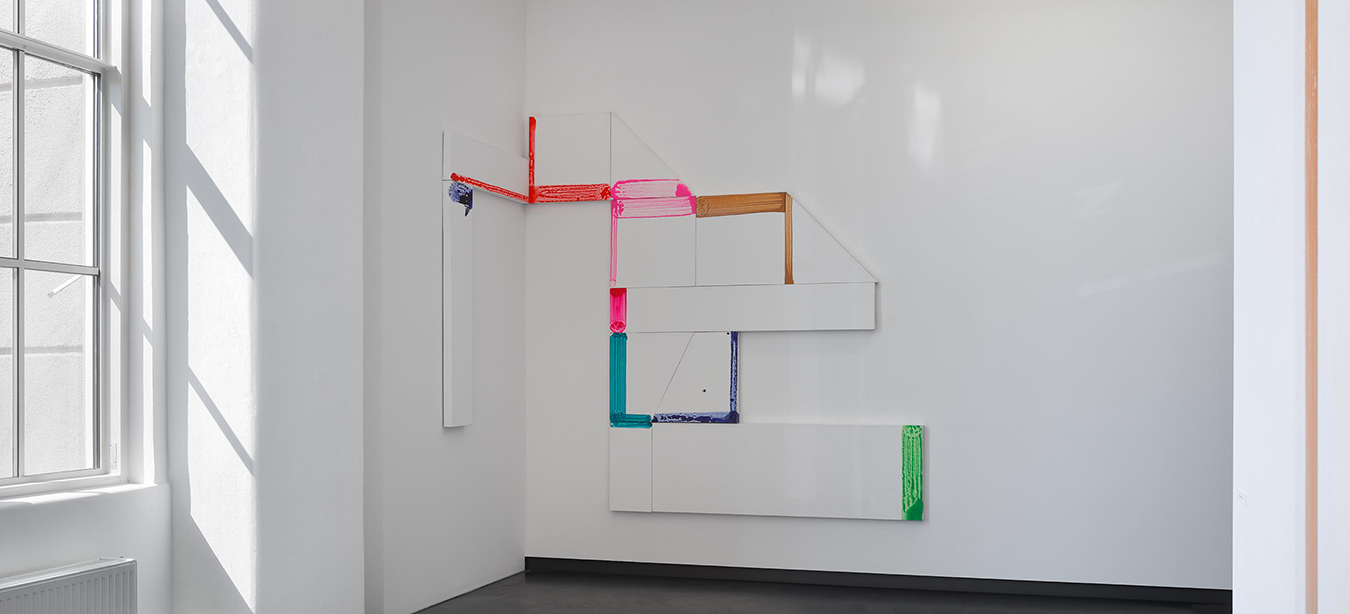

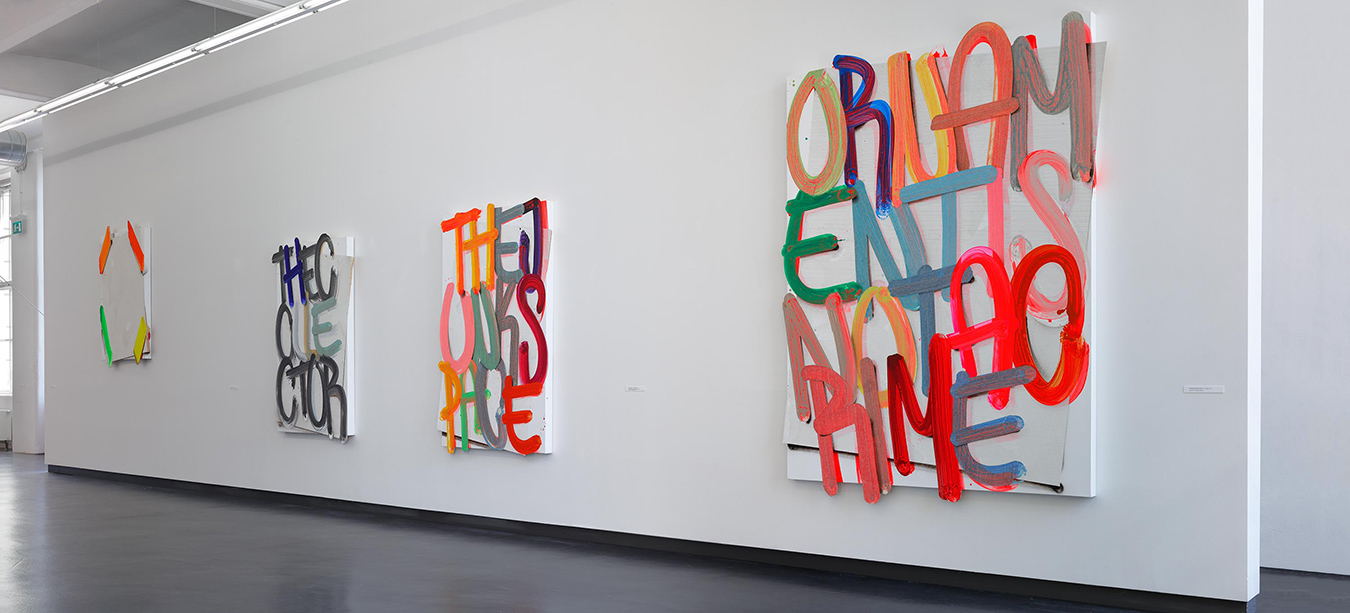

David Hanvald’s geometric minimalism is consistent with his idea of spatial presentations, as seen in works such as Bringing the Dream Home (with Priscila Fernandes and Jessica Stockholder in Krems in 2015). In this work, the strong reduction of the painting corresponds with that of the minimalist spatial installation. In the painted relief designed to match the proportions of the room, the artist extends the actual spatial setting in situ: a real window frieze in the wall forms a horizontal viewing slit just below the ceiling. By applying a relief of an illusionistic stairway to the wall, Hanvald integrates the glass blocks of the window frieze into his artistic intervention. Thus, his colored relief becomes part of the spatial situation, just as the space itself becomes part of the painter’s work – a striking example of the organic fusion of painting, sculpture, and architecture in the artist’s concept. As mentioned before, it is apparent that for David Hanvald it is also always about the act of painting itself, not only the creation of images as a result. This can be seen in the clearly visible brushwork, deliberately left as a trace of the brushes before our eyes. Apparently, this distinct characteristic functions as a sort of painted self-confession. As a result, beyond any impression of large-scale workshop production, his works always have something handmade and processual about them, something that smells of paint and is created directly at the studio. Another reference to his self-perception as a painter might also be the pictures reproduced in this book, which depict crayons and painting utensils in a cup in still-life style (pp. 154–155). In other cases, cubes become painted bodies standing, leaning, or lying in space like oversized, colorful boxes, building blocks, or abstract furniture. Even in their miniature form, the sketchy compositions, preserved in plexiglass boxes like tabernacles, leave no less of an impact than does an oversized, minimalisti-cally colored rolling cabinet or a space-filling cube suspended in a chapel vault. In his Text Paintings series, including works such as Green Deal, Cartel, CO2 (all 2019), SARS CoV 2 (2020), and Gas (2022), there are even subtle allusions to virulent contemporary topics, whereas Gian Lorenzo Bernini (2020) plays with art history again. Current events seem to only graze Hanvald’s painterly cosmos anyway, not really affecting it, much less being able to alter it in any way. The geometry he uses as a timeless framework is ornamental and unencumbered. Hanvald breaks down the constructive elements in a painterly manner, only to assemble them again in an equally virtuoso manner like building blocks. Within his cosmos of ornamental geometry, the painter acts playful and with a great richness of variation as well as a palpable delight in his own doing, thus dissolving any constructed severity in favor of free-floating visual experiences.

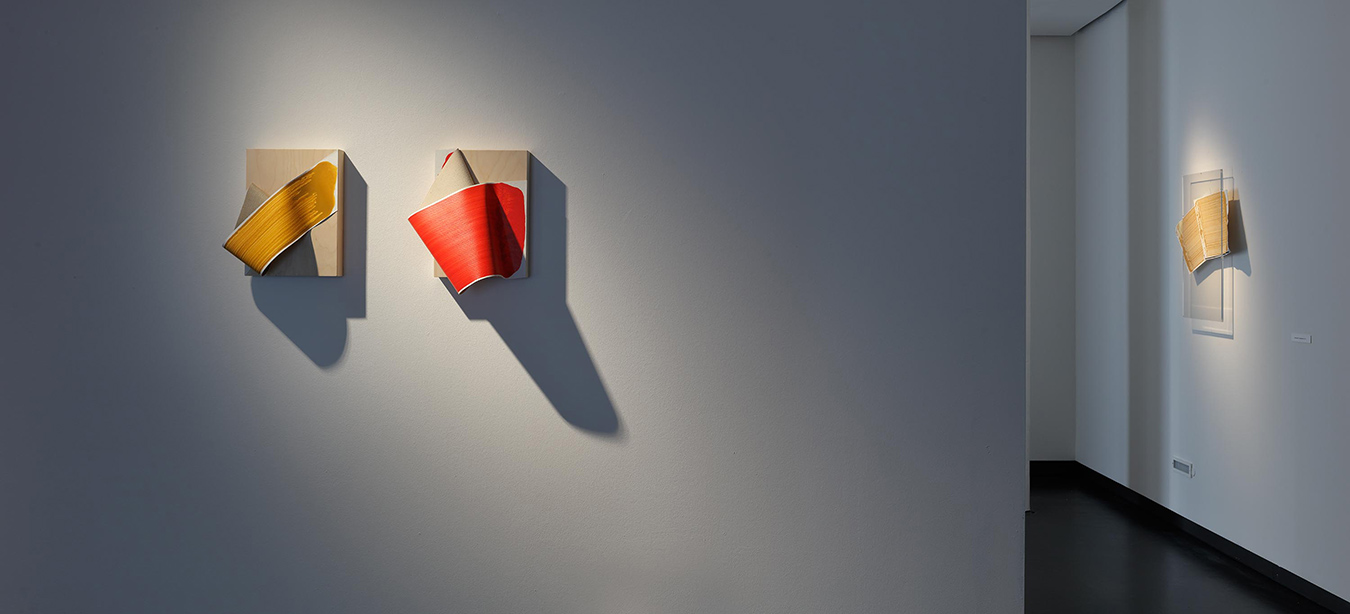

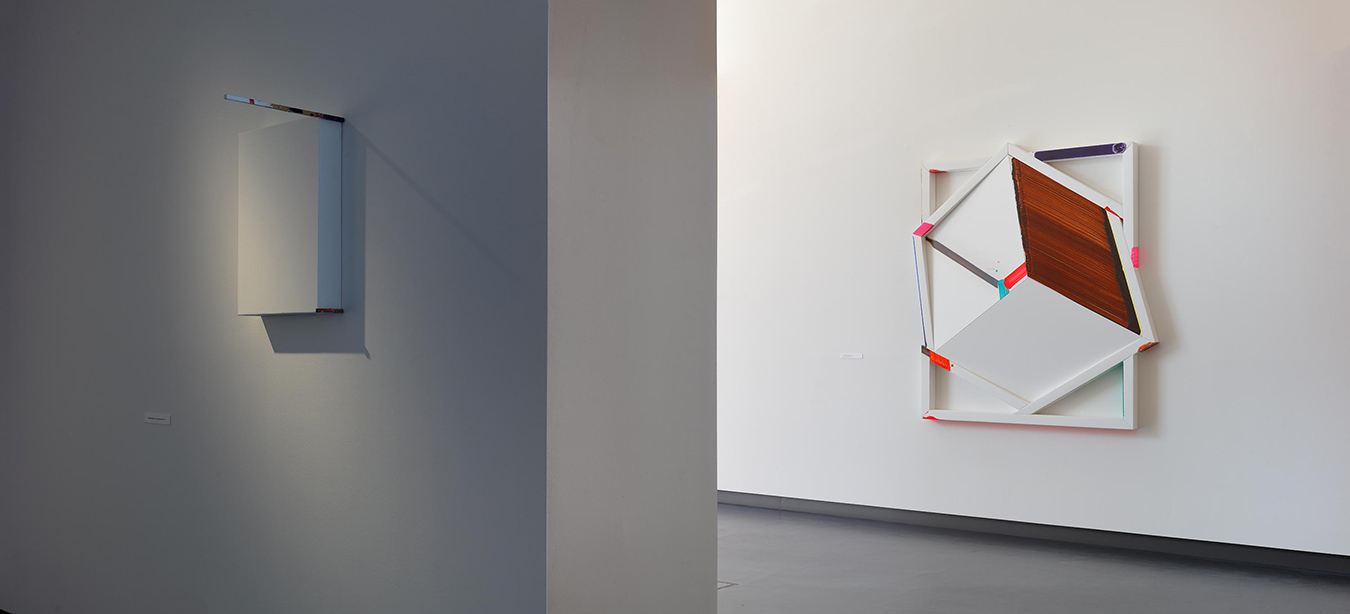

David Hanvald is a painter of geometric structures, which he positions with great clarity in relation to the painting support. It is precisely this relationship between pictorial object and painting support that is constantly redefined and questioned by Hanvald. Sometimes the support is a classic white canvas, sometimes it is broken, fragmented, sometimes it extends beyond the limitations of the canvas; and at other times his pictorial structures become even sculptural or installative. Hanvald’s paintings are powerful. Mostly, broad brushstrokes are placed on the canvas in a clear geometry. Without corrections, and almost meditatively, the color strokes spread across the canvas, forming the geometrical compositional framework. However, these structures do not always adhere to the limits of the canvases and wooden panels. In some compositions, the brushstrokes dissolve the boundaries of the painting support by extending beyond it. The painter creates this characteristic effect by continuing the contour of the brush stroke and creating a new ground for it. Concretely, he carves a shape out of wood that follows the contour of the brushstroke and connects it to the canvas. This creates a three-dimensional effect, or, in other words, the painting is literally breaking through the boundaries of the canvas. This reaching beyond the canvas creates a new space in between painting and wall. Or, to put it another way: the painting is thus capable of casting a real shadow on the wall. In this way, the materiality of the image and of the painting reaches a new dimension. With this three-dimensional effect, the place where the picture is shown also becomes charged with meaning, because the very wall displaying the picture thereby gains constitutive significance for the painting. Thus, space and paintings are linked in a close interdependence. David Hanvald opens up new spaces for painting, dissolving its boundaries. His brushstrokes can therefore be understood as a liberation of the paint from the canvas, which, however, always remains closely connected to it. Painting becomes a medium of the dissolution of boundaries.

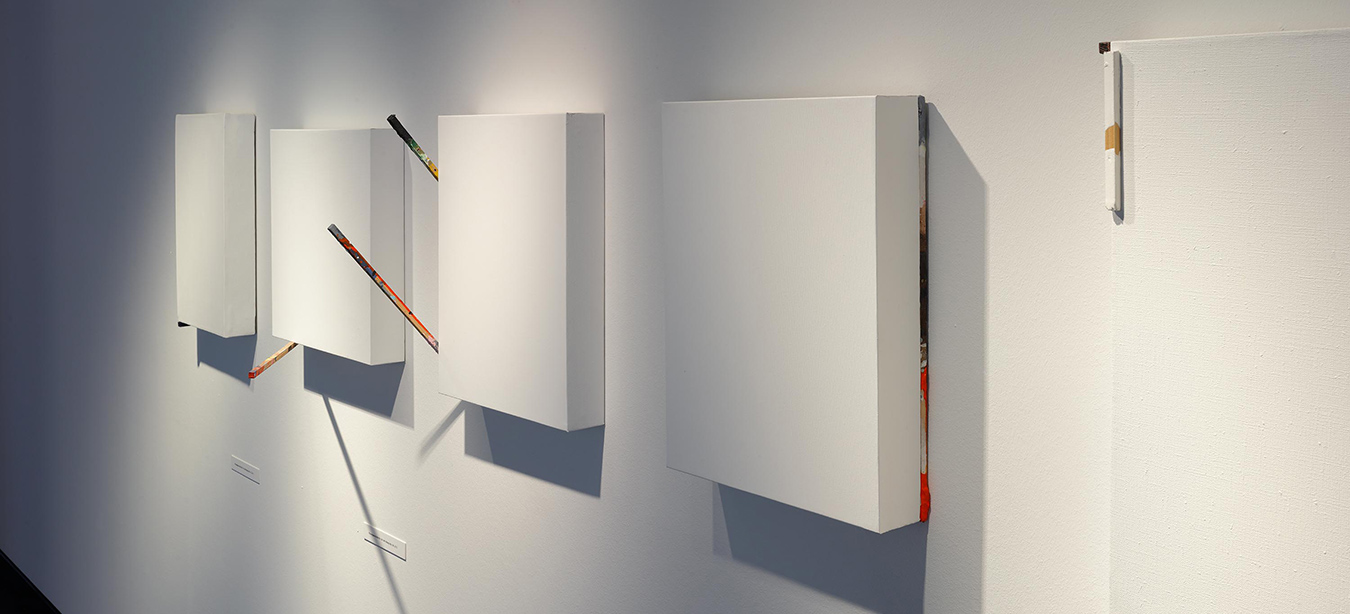

The fact that Hanvald has been seeking such a dissolution for quite some time is also demonstrated by his homage to Sol LeWitt, an American conceptual artist who has also devoted himself to geometric structures (p. 36). In his 2010 exploration of the American painter, Hanvald still remained in the two-dimensionality of the canvas. He created three-dimensional effects by suggestively combining color strokes into grid structures and cubes – an associative attempt to approach Sol LeWitt’s visual potential. Through this subtle approach, he infused the color structures with a particular spatiality and three-dimensionality. In his installations, Hanvald takes this a step further by making paintings spatially tangible on cubic painting support, cubes, blocks, panels, and steles (p. 82–83). He piles blocks of white color, which he paints with minimal brushstrokes. Often, he accentuates edges and corners with broad streaks of color, thus emphasizing their geometry. Then, in a second step, he positions these blocks and steles against walls, placing or hanging them in the corners of the room as if by chance. Particularly the latter areas are of great importance to him, since in room corners, the three-dimensionality of a room crystallizes in a special way. In these installative works, Hanvald responds to the environment, meaning that he works with real spaces by making it visible through his paintings. David Hanvald is not only a painter of dissolving boundaries; he is also a painter of spaces, who tries to be very aware of the position from which he acts.